The History of Media Use in Peacebuilding

The History of Media Use in Peacebuilding

07/04/2015

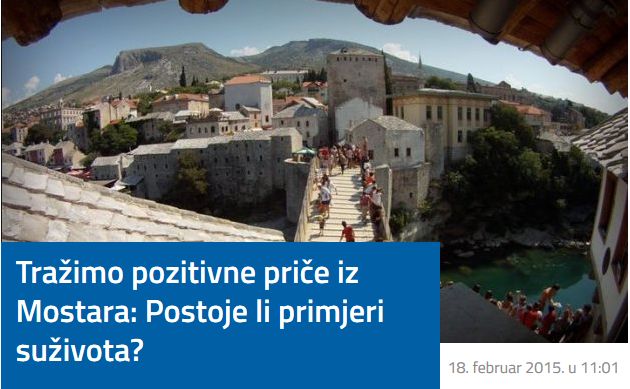

In February of this year, Radio Free Europe broadcasted a series of documentaries from the city of Mostar about the lives of youth in the post conflict times. The series came as a shock to many citizens in Bosnia and Herzegovina because it pointed out the divisive attitudes and deep prejudices among its youngest citizens. Several high-school students featured in interviews maintained that they could not envision living with people from the opposite ethnic and religious group. These words were so shocking because they reminded many of the acrimonious rhetoric of the war times. The explicit kind of hatred was supposed to have been defunct 20 years after the end of the war.

Peace journalism

So when the deep ethnic divisions of the Mostar youth went viral across new and old media platforms, there was no shortage of responses; some were worried, others were witty but many more pointed that this is not a dominant belief of the citizens of Mostar and especially not of the majority of Bosnian society. One of the prominent new media portals, Radio Sarajevo decided to go a step a further and encouraged its readers to send in the stories that described the examples of the positive relationships and coexistence in the city. The stories poured in and the next day the portal published numerous accounts of personal friendships and close relationship among people in Mostar despite their ethnic and religious background.

What Radio Sarajevo did is what academic literature and international development practice define as peace journalism or peace media. Deliberately focusing on producing journalism and other media (e.g. entertainment, marketing and new media) in support of peace and coexistence in the time of conflict has been a major practical field of the international development over the last 30 decades. On the ground, the practices consists of a complex set of deliberate attempts to fund, organize and produce media content that helps societies in conflict resolve their disputes and transform violent conflict into non-violent negotiation in the political and civic arenas. The origins of the practice date back to the post World War II when the international community engaged in international development focusing on the problems of poverty, health development, disease prevention, family planning, etc. When the United Nations organized their peacekeeping mission in Cambodia and Namibia, they were the first organized entities to include media operations (a radio station in Cambodia and print and audio-visual materials in Namibia) into their formal peacekeeping operations.

Media-oriented peace projects

Post Dayton Peace Agreement, Bosnia and Herzegovina been a highly fertile ground for one of the most comprehensive peacebuilding efforts by the international community. Just one of the aid agencies, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), by their own account, spent more than $1.6 billion in post conflict for peacebuilding. They heavily invested in media projects like Open Broadcast Network (ONB), Radio FERN, Mreza Plus, PBSBiH and most of the commercial media in Bosnia benefited directly from funding, training and equipment donation by the international aid agencies. The donor community was under impression that since media were suspected inciter of the war they must play an integral role in peacebuilding.

Photo: Screenshot/Radio Sarajevo

Number of other violent conflicts of the era saw a fair share of similar media-oriented peace projects. In post-genocide Rwanda in the late 1990s, one of the most popular media programs listened to by 80 percent of people was radio soap opera – a story about Hutu and Tutsi families living next to each other and a subsequent love story across the ethnic lines. In Northern Ireland, after the Good Friday Peace Agreement in 1999, media campaign was launched by a leading public relations firm McCann Erickson. The PR agency bombarded the citizens of Northern Ireland with the messages about benefits of peace though billboards, direct mail and radio-TV spots. When the Internet and mobile technologies became the widespread tools of mass communication, they were quickly coopted for peacebuilding purposes: In Kenya, at the time post-electoral violence in 2009 a small group of people (Ushahidi) organized an online platform that mapped and thus warned about instance of violence on the ground. What was new at the time was the documentation of those violent acts came not from journalists but directly from the citizens via SMS. Finally, the practitioners implementing peace-oriented media soon realized that eliminating the propaganda, hate speech and threats to journalist were as important as producing positive media. This was why many countries in their post-conflict recovery focused on establishing media laws and regulatory agencies, like the exemplary CRA in Bosnia and Herzegovina or IMC in Kosovo.

Four major practices

So what came of the diverse practices after 30 years of practice is now fairly apparent set of four major practices where media proved to be effective peacebuilding partners and those are: journalism, other media (entertainment and marketing), new media and regulative system of laws. Good journalism is essential to peace because when done competently it performs a number of functions that curb the power of conflict promoters and benefit the society in general. This is why most funding of the last years has been spent on strengthening professional journalism via training, support of independent media, and pluralization of media outlets. Entertainment is often considered an insignificant past time activity and rarely thought of as a tool for political change. However, ability of entertainment shows to change the attitudes, affect the values and prime the audience toward reconciliation has been widely underestimated. Marketing is another practice that has skillfully targeted major obstacles to peace. Demining campaigns, promotion of repatriation rights of refugees, advocacy for adoption of peace agreements are just a few marketing campaigns that have been skillfully conducted and produced positive results. New media is still an unknown entity; there are as many instances of promotion of peace online as there are promotions of conflict. However, formally organized peace NGOs have found ways to utilize the new technologies (mobile, social media as well as the general Internet) to enhance their ability to affect conflict. Satellite monitoring of the conflict zones, crisis-mapping of humanitarian needs in conflict, activist campaigns on social media and increasing citizens' participation in reporting though blogging, video, SMS technologies are all positive new developments for peacebuilding. Finally, despite all the positive developments over the last 30 years propaganda, hate speech, violence against journalists and control of media remain the major obstacles to a lasting peace. These obstacles to peace are unlikely to be eliminated by journalism, marketing, entertainment or innovative new media. Instead, only comprehensive regulative system of media laws can do that. Therefore, complete practices requires combination of media laws against hate speech, codes of conduct for journalists, defamation and libel laws, as well as regulatory bodies capable of monitoring and enforcing those laws.

The history of the last three decades of media use in peace have taught us that media has a potential to play a constructive role in conflict. This is a fairly new and positive development. As long as we can remember, media have been primarily in service of powerful parties who used to extend their influence and that often meant promotion of conflict goals. From Roman armies' use of primitive media to Hitler's propaganda techniques; media has been serving the centers of power as a passive tool of mass communication. Luckily, the power of large corporations or tyrannical regimes to control media and censor speech has been weakening. The last thirty years are positive departure from this tradition. After the Cold War, media technologies have become much more portable, easier to operate, cheaper and widely available. For the first time in human history, citizens have ability to operate mass media outlets. Many NGOs have helped build radio stations, television networks, support newspaper outlets because today's mass media does not require bulky equipment, expensive resources or high level of expertise. Anyone with a phone and a blog or a social media account has the potential to become the source of mass information. Additionally, the most recent merging of mobile and social media technologies allows people to cooperate across national border and across age, gender and income divides. Formerly passive audiences are becoming active participants in civic affairs. These are exciting times for peacebuilding activists and civil society. But this also means empowerment of regular citizens to share their experience. So citizens' positive stories countering the conflict narrative like the ones from Radio Sarajevo's reaction to the situation in Mostar are likely to be become a norm rather than an exception. All in all, we are all much better for it.