Protecting the Sources Who Keep Journalism Alive

Protecting the Sources Who Keep Journalism Alive

Aidan White, a former journalist with The Guardian who led the International Federation of Journalists for 23 years and the founder of Ethical Journalism Network, explains for Mediacentar why reporters and editors need to protect the people who give them information

News happens all the time. Banks are being robbed, cars are crashing, people are dying, goals are being scored, crimes are being committed and politicians are up to no good.

Journalists can’t be everywhere to witness these events for themselves, so they rely on others to provide them with the facts, eye-witness testimony and insider secrets they need to tell their stories.

These are our sources of information. They are the lifeblood of quality journalism. Reporters may be stylish writers or polished presenters, but what counts most to the public is the reliability of the stories they tell, and that depends on the quality of our sources.

These may be people with their own stories to tell, or who are experts and insiders. They may give us testimony or written reports or confidential documents, even pictures or recordings – all potentially vital in exposing corruption or wrong-doing in public life.

Sometimes people take huge risks to give journalists information that the public needs to know. Edward Snowden, for example, worked with the National Security Agency (NSA) in the United States, and he became a heroic friend of journalism and democracy when he blew the whistle on how the United States government was engaged in a process of mass surveillance across the globe.

Snowden released thousands of documents providing secret information to journalists in the United States and Britain about the scale of the surveillance, including how the NSA was even snooping on the leaders of other countries, by listening to their phone calls.

He became a public enemy in the US and is now a fugitive, living in Moscow. But the information he gave to responsible news media about America’s secret shadowing and interference in global communications has made the world a safer place.

Journalists are always in debt to the heroism of whistle-blowers like Snowden when it comes to exposing the abuse of state power. I had my own experience of this when working at The Guardian in London.

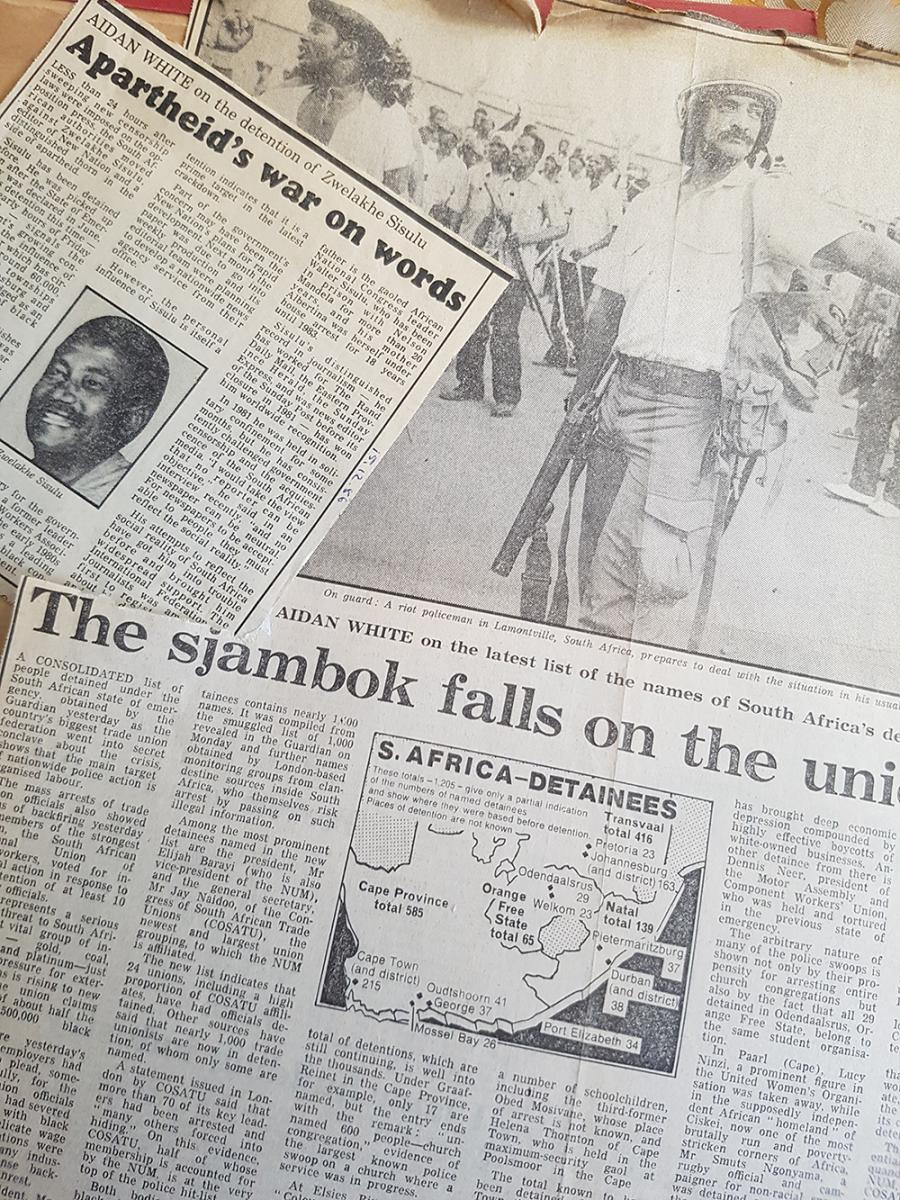

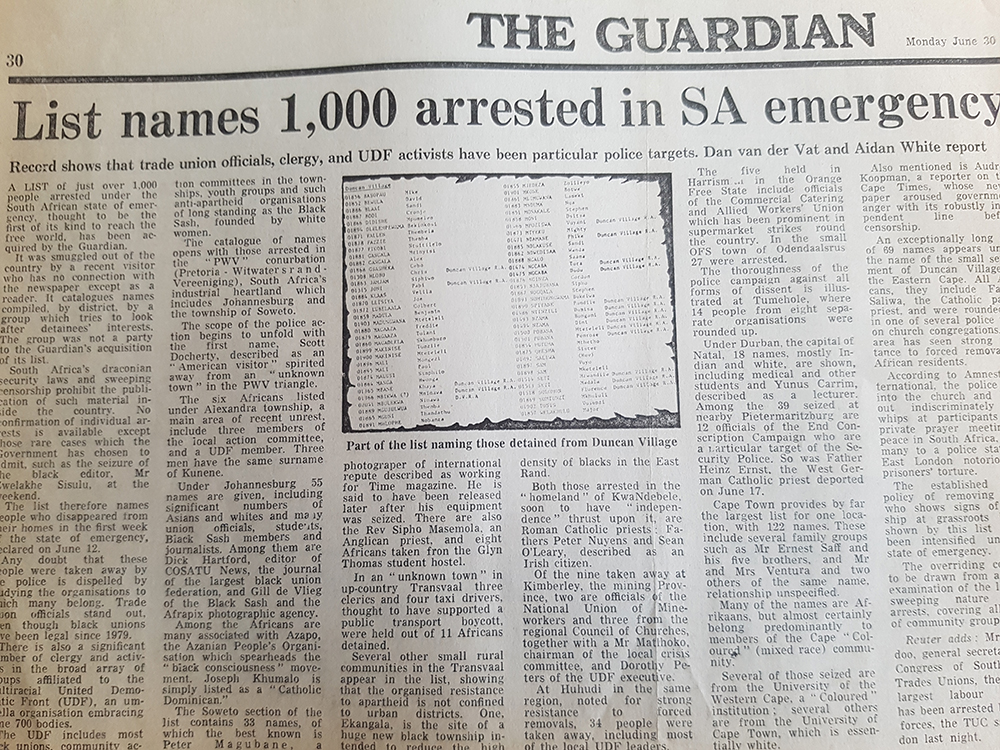

During the 1980s I reported on the struggle against the apartheid regime inside South Africa. As internal resistance to the white regime intensified, the government panicked and in 1986 declared a state of emergency, suspending democratic rights and the rule of law and launching a massive campaign against the anti-apartheid movement. I followed this closely and reported on the arrest and detention of South Africa’s leading black journalist. While working on the story I was given a secret document containing a hit-list of more than 1,000 people targeted by South African security services.

During the 1980s I reported on the struggle against the apartheid regime inside South Africa. As internal resistance to the white regime intensified, the government panicked and in 1986 declared a state of emergency, suspending democratic rights and the rule of law and launching a massive campaign against the anti-apartheid movement. I followed this closely and reported on the arrest and detention of South Africa’s leading black journalist. While working on the story I was given a secret document containing a hit-list of more than 1,000 people targeted by South African security services.

The list included the names of trades unionists, church leaders, students, teachers, lawyers, journalists, and scores of local activists. They came from all sides of the community; united by a common loathing of the apartheid state.

The information came into my hand thanks to the bravery of people inside South Africa, who not only compiled this list but risked their lives to smuggle it out of the country.

We examined the list and verified the names as best we could and The Guardian published it, a worldwide scoop, revealing to the outside world for the first time the scale of the crackdown in South Africa and how many lives were threatened.

Our sources remained hidden. We did not disclose who they were or where they came from. If we had done so, their lives would have been at risk. We explained this to our readers.

Whenever journalists get potentially explosive information like this they have an ethical duty to provide the sources with protection. Someone might lose their job, or their life, so we have to keep them safe.

But sometimes that’s easier said than done. In my 50 years or so, working as a journalist and a campaigner for journalists’ rights, I have found myself in many situations where source protection has been under attack.

My first brush with the law over sources was as a fresh-faced cub reporter in the 1970s working on the Peterborough Standard a local newspaper in a small town in the midlands of Britain. I came across a story about a drugs ring centred on a local nightclub. I got inside information about the ring from a couple of people working inside the club.

I checked it out, assembled the quotes and prepared the story. It made the front page, but I kept the names of my sources out of the story. They were worried they would lose their jobs.

The next day the editor called me into his office where he was sitting with the local police chief who wanted to know who I had talked to. I said I couldn’t tell him but I hoped the story would give the police enough leads to make their own inquiries.

To my surprise, the Editor asked me to hand over my notebook, which contained all of the facts of the story including details of the people I talked to. He handed the notebook to the police chief.

This incident taught me to improve my own security systems. Notebooks (and tape recorders) are for quotes and uncontroversial background information, but the personal detail that identifies a source has to be kept in a safer place.

lt also taught me that the person responsible for protecting sources is the journalist writing a story and not his boss, not even his editor. A journalist may tell their editor who they are getting information from, but sometimes it is too risky to let anyone know.

An editor can decide to publish or not, but the final decision about confidentiality must rest with the individual journalist who makes the arrangement in the first place.

This experience was an early and painful lesson in ethical journalism, but did not lead to any problems for my sources. The police carried out their investigation without doing them harm, and the illegal drugs trade in at least one backstreet of Britain was closed down.

My time on The Guardian also saw headlines over an infamous moment in the recent history of British journalism when the paper in 1983 blundered over the protection of a source which led to a public-spirited young woman being sent to jail.

She was Sarah Tisdall, a 23-year-old Foreign Office clerk. While photocopying a document, she noticed that it contained a secret plan by the government to divert public attention from the controversial arrival in Britain of Cruise nuclear weapons from the United States.

She realised immediately this was a shocking abuse of power, so she sent a copy of the documents anonymously to The Guardian in an unmarked envelope. The paper splashed the story on its front page.

But then, instead of destroying the original documents, which provided the only way of tracing the source, the paper kept them and then refused to hand them over to the security services. The paper fought a court case against the government, arguing the defence of press freedom, but they lost the case on appeal, and the editor, facing heavy fines or a possible jail term, handed the papers over.

To the paper’s embarrassment, the leaker was unmasked, sacked and prosecuted for having broken Britain’s Official Secrets Act, an act of law notorious for its protection of undue government secrecy and wrongdoing. She went to prison for six months.

Although The Guardian offered her compensation and a new job when she was released, she refused and went on to work in defence of human rights elsewhere.

During these events I was the leader of the journalists at The Guardian who argued that the paper and its editor must uphold the cardinal principle of the journalists’ code – to protect our sources of information. Our union said that this was so important that journalists should be ready to go to jail rather than betray a source, even an anonymous one.

But the paper’s editorial management, after much hand-wringing and internal discussion, decided to give up the source. It was a low point for ethical journalism, and one which could have been easily avoided if the documents had been destroyed after publication. Another hard lesson, and one that The Guardian and every other national newspaper in Britain remembers to this day.

___

Želite sedmični pregled vijesti, analiza, komentara i edukacija za novinare u Inboxu Vašeg e-maila? Pretplatite se na naš besplatni E-bilten ovdje.